Those who believe the Earth is flat may truly desire to live in a fantasy world.

In late January of this year, rapper B.o.B. took to Twitter seriously wanting to know why everyone thought the Earth was a sphere. Neil deGrasse Tyson, designated king of space, let B.o.B. know several ways that he could observe the Earth’s curvature for himself. For a man who can sometimes be a little overzealous in trying to apply science to character-based fantasy narratives, Neil took it pretty easy on B.o.B. Perhaps he knew that B.o.B. willingly dropped out of high school in the ninth grade, and probably missed the basic education in science that would have given the rapper the deductive tools needed to understand the mechanics of his world.

Neil probably also knows that one of our most beloved sagas, J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, begins on a flat [Middle-]earth, and that there is considerable mystique in the idea of a flat planet.

Even after B.o.B. released a meandering diss track, Neil kept it cute with a mic drop response on Larry Wilmore’s Nightly Show. The diss track is gone now and the matter seems(?) to be closed, with Neil and common sense prevailing. And yet, the members of the Flat Earth Society maintain their membership in the Flat Earth Society. There is clearly a strong allure to the idea of a disc-shaped planet.

Tolkien must have thought so, too, as his creation mythology of Middle-earth begins with the planet as a flat circle. This physical realm was known as Arda*, and well before the time of hobbits and rings, it was “sung” into being by the Ainur, the first creations of Eru Ilúvatar, the Creator of all things. Some Ainur showed interest in having a caretaking role over the newly created Arda and its denizens, including Elves and Men. These Ainur took physical form and dwelled on the flat planet, becoming Valar and their counterparts of lesser power, Maiar. To put this in perspective, the people that we know of as Gandalf, Saruman, and Sauron are all Maiar. And as we see in The Lord of the Rings, even a “lesser-powered” Maia like Sauron is still strong enough to warp Arda and bring about the near-extinction of entire species of beings.

*The definition of Arda changes as the structure of Tolkien’s cosmology changes and can also refer to the cosmos that the planet exists within. For the purposes of this article, Arda refers to only the planet itself.

Sauron didn’t generate his dark arrogance all by himself. He had a teacher in the form of Melkor (also known as Morgoth), one of the Valar who, during the creation of Arda, sang a counter-harmony to the chorus of creation that his Ainur brethren were fashioning. Because of this, chaos and entropy were sewn into the reality of Arda, and Melkor became so enamored with the chaotic physical realm of Arda that he came to live within it and eventually proclaimed that it belonged entirely to him.

In summary, Melkor/Morgoth is basically that guy in the car who insists on singing his own lyrics to “Bohemian Rhapsody.” And Sauron is enamored with him.

The Arda that Melkor initially claimed was a pretty boring place: a flat circle of land with a round sea in the middle and an island in the middle of that, much like an eye. Surrounding this flat circle of land was an Encircling Sea, which was itself surrounded by the Void.

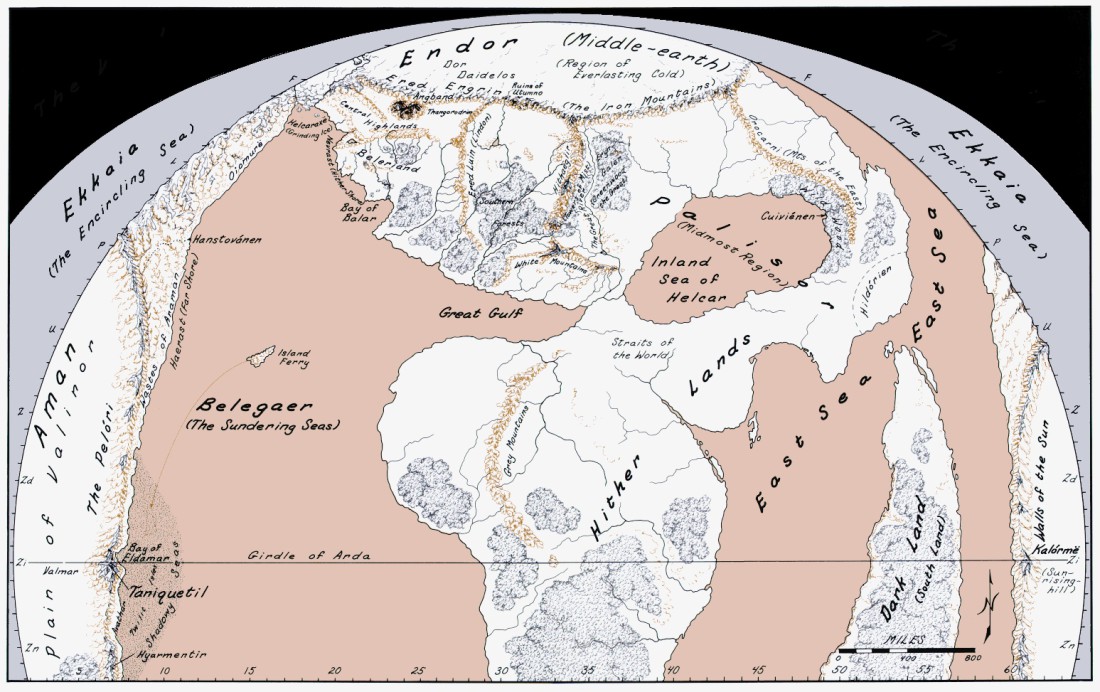

Arda did not stay this way. The battles between Melkor and the rest of the Valar were numerous and repetitive. Melkor would mar the land, raising mountains or creating gaps that the Encircling Sea would rush into, before he was overpowered and banished into the Void. Then he’d find his way back and continue his process of alteration before being turned away again. Over time, these struggles produced a flat Arda with several continents on it, as imaged in The Atlas of Middle-earth by Karen Wynn Fonstadd.

Melkor and his servants took strongholds in the northern continent—the one we know as the Middle-earth that Tolkien’s main series takes place upon—while the forces of the Valar held the western continent of Valinor, which would later come to be known as The Undying Lands. Melkor (really, Morgoth at this point) held the central continent for the entirety of the First Age of Arda, a span of almost 600 years, before he and his servants were finally crushed by the Valar, and the First Age of the world was drawn to a close.

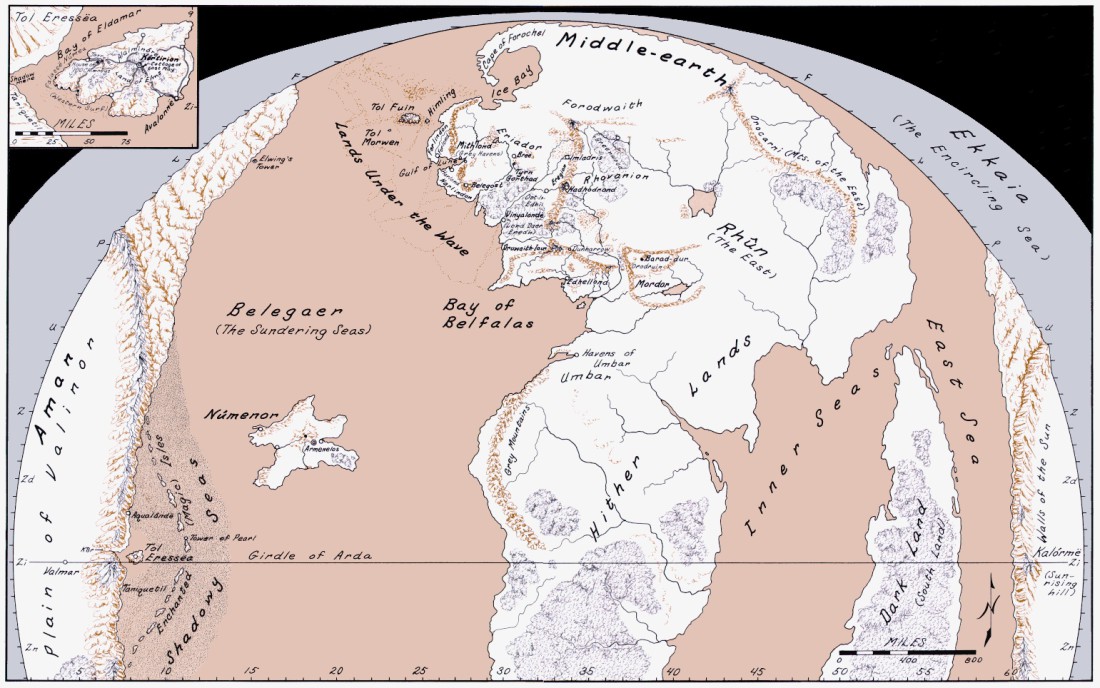

Even in defeat, Morgoth’s purpose remained fulfilled, for he marred the land so greatly that the Valar spent the dawn of the Second Age changing the landscape even further in order to correct this marring. The northern and southern continents were further merged, Mordor was formed, and an island known as Númenor arose from the Sundering Seas.

With Morgoth gone, his devotee Sauron rose to prominence and began his long bid for power, taking lands, swaying men, and forging some very familiar rings within the span of about 1500 years. In fact, Sauron’s hold on Middle-earth is maintained until the year 3446 in the Second Age, when Isildur defeats Sauron and has that awesome shouting match with his best bud Elrond.

In Tolkien’s legendarium, the entire history of Arda leading nearly up to the events that inspire the War of the Ring has taken place on a completely flat planet surrounded by a sea, ringed by a void. This kind of setting is certainly atmospheric, and helps to deliver an epic scope to the history leading up to The Lord of the Rings. On a flat, enclosed disc of a world, wars between demigods like Melkor, Sauron, and the Valar truly determine the fate of all.

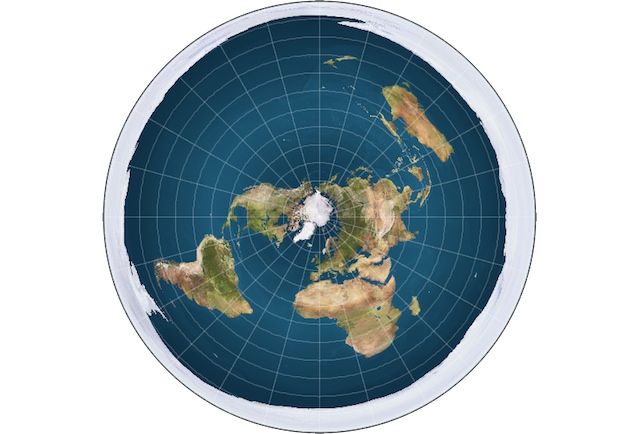

This kind of setting, one that makes the world knowable and inescapable, seems to appeal to those believe in a flat Earth, as well. Ashley Feinberg at Gawker summed up the various workarounds that Flat Earthers use to explain everyday phenomena, and the list reads similar to considerations Tolkien made when constructing the beginning of Arda and Middle-earth.

Flat Earthers postulate: The firmament, a solid dome sky with the Sun, Moon, and stars embedded within it.

Tolkien postulates: The void, an open space around Arda where the Sun, Moon, and stars move on their daily trajectories above and below the flat disc of the planet.

Flat Earthers postulate: The ice wall, a pitch black, absolute zero barrier that surrounds the disc of our flat Earth and which can’t be voyaged beyond.

Tolkien postulates: The Encircling Sea, which can be voyaged upon and passed through, although if you’re of the race of Men, that will hastily result in your death.

Flat Earthers postulate: A vast conspiracy between world governments (who always famously get along) and NASA to falsify evidence of a round planet for… reasons?

Tolkien postulates: An unimaginative God-being that keeps getting its nice flat featureless planet messed up by its children, one of whom is literally just trying to make his own stamp upon the world.

Flat Earthers postulate: Universal Acceleration instead of gravity. Basically, that our flat planet is flying through a plasma-like medium called “aether” face-first, pressing all of us down onto the surface of the Earth. Why this is necessary is unclear, since a flat planet with a domed underside would still be plenty massive enough to keep us grounded via gravity.

Tolkien postulates: No flying creatures. Except eagles, friendly thrushes, dragons, black arrows, fellbeasts, that one moth Gandalf keeps whispering at, and Gimli when being tossed. Okay, so lots of flying creatures, but also gravity. Because Arda does have a domed underside, called “Ambar.” Presumably, Tolkien including this in his cosmology presented no problems.

The parallels between Tolkien’s world-building and Flat Earth beliefs can be very direct when listed out by feature. To those who believe in a Flat Earth, these parallels may simply be further confirmation that our real world is capable of existing as a disc instead of a sphere. Tolkien’s world certainly feels real to its readers, after all, and the author was exhaustive in detailing its history, its composition, its language, and even its future. Perhaps Tolkien was a Flat Earther himself, and was simply seeding in the truth of things through his epic tale…

Except that even Middle-earth eventually became round. Around one hundred years before Isildur battled Sauron, the dark lord wheedled his way into power on the island of Númenor, stationed halfway between the Valar’s Undying Lands and Middle-earth. For one Vala in particular, this was the last straw. Manwë, brother of Melkor, asked the Creator itself, Eru Iluvatar, to make an example of those who would ally themselves to Sauron. The Creator obliged, sinking Númenor, making the flat Arda into a sphere, and severing the continents of the Valar’s Undying Lands from Arda. A man (or woman, or elf) could leave from the Grey Havens in the west and sail all the way around the globe, eventually hitting the lands east of Mordor.

With The Undying Lands inaccessible, Middle-earth was now alone on the planet of Arda. The new spherical world stood as both a warning and a gift: do not let dark prophets misguide you. For if you succeed in casting off their sway, then the Fourth Age, the Age of Men, will ensue and this world will be yours to sculpt.

In crafting his fictional world, Tolkien gets to the very heart of why Flat Earth beliefs feel so offensive. It isn’t just the ignorance that these beliefs champion, or the refusal of the gift of knowledge that previous generations grant to us, but the limitations that beliefs like this impose upon others. By being so dedicated to the fantasy of a Flat Earth, a believer is insisting that the expression and ingenuity of mankind is limited to two dimensions, that the horizon is impassable, that we are stuck in our ways.

This is a hopeless way to see the world. And perhaps this is one of the reasons why we construct such elaborate fantasies through art and literature, not to close off possibilities within our own lives, but to illuminate the straight way out of such hopelessness.

Chris Lough writes about fantasy and superheroes and things for Tor.com. Over time he has also gone from flat to spherical.